What Alexander Hamilton Really Said

Ever since Donald Trump was elected President, there’s been lots of discussion—and some disagreement—about the Foreign Emoluments Clause. Despite the disagreement about various aspects of the Clause, one aspect of it hasn’t been the source of much disagreement. Most people, including even the President’s own lawyers, agree that the Clause applies to the President.

And no wonder: by its terms, it applies to the President, barring all persons “holding any Office of Profit or Trust” under the United States from accepting benefits from foreign states. And it would have been odd for it not to apply to the President, given the Framers’ deep concerns about corruption and foreign influence. Indeed, they talked about it applying to the President: at the Virginia ratifying convention, Edmund Jennings Randolph said that “[t]here is another provision against the danger mentioned by the honorable member, of the president receiving emoluments from foreign powers. . . . I consider, therefore, that he is restrained from receiving any present or emoluments whatever. It is impossible to guard better against corruption.” And Congress and the executive branch have thus long assumed that it applies to the President.

Yet a small group of commentators has nonetheless maintained that it does not apply, or at least may not apply. The leader of this group of naysayers is Seth Barrett Tillman, who has argued forcefully—and repeatedly—that the Foreign Emoluments Clause’s broad language does not encompass the President of the United States. Although Tillman makes more than one argument in this fight, he has often leaned heavily on one particular piece of evidence: a list of “persons holding office under the United States and their salaries” put together by Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton that, he says, “did not include any elected officials in any branch.” According to Tillman, this document demonstrates that “officers under the United States are appointed; by contrast, the president is elected, so he is not an officer under the United States. Thus, the Foreign Gifts Clause, and its operative office under the United States language, does not apply to the presidency.”

Tillman pointed to this document here and here and here, and others have understandably relied on his accounting of the Hamilton document. Most recently, Tillman pointed to it in an amicus brief in support of the government’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit filed by CREW and others in the Southern District of New York.

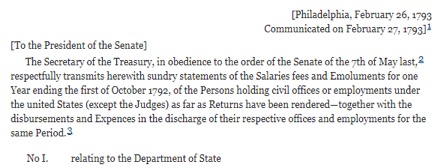

But there’s a big problem: the document Tillman cites is not the only record of Hamilton’s communication to the United States. The document Tillman cites states, “The Secretary of the Treasury, in obedience to the order of the Senate of the 7th of May last, respectfully transmits herewith sundry statements of the Salaries fees and Emoluments for one Year ending the first of October 1792, of the Persons holding civil offices or employments under the united States (except the Judges) as far as Returns have been rendered . . . .” The editors of Alexander Hamilton’s papers added a footnote explaining that there was, as Hamilton’s letter indicated, an enclosure—the actual list of officeholders and their respective compensation. And as the footnote further explained, while “[t]his enclosure, consisting of ninety manuscript pages, has not been printed,” an “abbreviated version of it” is available in the American State Papers.

When one looks at the “abbreviated version” of the enclosure (available here at image 57), one name is right at the top: George Washington, President of the United States. John Adams, as Vice President, appears right below his.

And then the document proceeds to list the officers in the various federal agencies, just as in the document that Tillman has been repeatedly referencing for months. Whatever the exact relationship between these two documents, it seems stunning to point to one, without acknowledging the other. Yet that’s exactly what Tillman has done. Repeatedly.

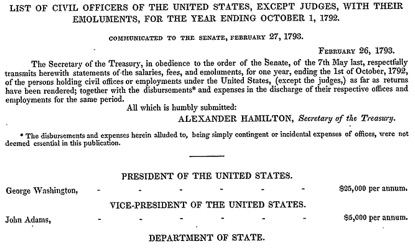

Recently that changed. In his amicus brief Tillman again relied on this document from Alexander Hamilton, explaining that Hamilton’s response “spanned some ninety manuscript-sized pages,” and that “[i]n it, he included appointed or administrative personnel in each of the three branches of the federal government,” but “did not include the President, Vice President, Senators, or Representatives.” Thus, he says, “the Hamilton document is another probative Executive Branch construction of the Constitution’s office under the United States-language.”

This time, he did at least acknowledge the existence of the document that does include George Washington—kind of. According to Tillman, there is “an entirely different document (but bearing a similar name)” in the American State Papers. This document, he says, “was not signed by Hamilton.” This document, he says, was “undated.” This document, he says, “was drafted by an unknown Senate functionary.” This document, he ultimately concedes, is “probative of the legal meaning of Office . . . under the United States,” but not as probative as the other document on which he has repeatedly relied.

Perhaps if his characterization of the American State Papers were accurate, he would be right to give it less weight. But it’s not accurate, not even remotely so. To start, the document is not, as he says, “entirely different.” To the contrary, as noted earlier, the editors of Alexander Hamilton’s papers—the source Tillman cites for the Hamilton document on which he relies—identified the American State Papers document as an abbreviated version of the enclosure attached to Hamilton’s letter. Indeed, the introductory paragraphs of both documents are essentially the same, as the graphics below make clear. The document is also not, as he says, undated. It’s dated February 26, 1793—the same date as the source on which Tillman relies. This document is also not, as he suggests, the errant document of some “unknown Senate functionary.” Even if not literally “signed” by Hamilton—the document is typeset and printed, not handwritten—it plainly is Congress’ record of the official response from “Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury” to the same Senate inquiry to which Tillman’s document was a response. (Again, Tillman claims these are two “entirely different” documents.) In sum, after months of pretending like this document didn’t exist, he finally acknowledged it—and was forced to describe it in grossly misleading terms in order to discount its significance.

To be sure, the Hamilton document is not the only basis for Tillman’s argument that the Foreign Emoluments Clause doesn’t apply to the President, and his ultimate conclusion about the scope of the Clause is wrong for lots of reasons beyond the existence of this American State Papers document. But he’s placed a lot of weight on this document and what Alexander Hamilton supposedly didn’t say in it. So it’s important to know everything Hamilton did, in fact, say—including that George Washington was a person holding an “office[] under the United States.”

Beginning of Tillman document (as transcribed):

Beginning of American State Papers document: