A Little More on Alexander Hamilton and the Foreign Emoluments Clause

Earlier this month, I wrote a piece for this blog on the debate about whether the Foreign Emoluments Clause, which applies to all persons “holding any Office of Profit or Trust” under the United States, applies to the President. As I explained in that piece, there’s a “big problem” with one of the major pieces of documentary evidence relied on by those who argue that it doesn’t apply. My colleague Brian Frazelle and I have now done a little more digging, and the problem with that evidence has gotten even bigger.

To briefly recap: most people agree that the Foreign Emoluments Clause applies to the President, but a few—determined to engage in an uphill battle against both the language and purpose of the Clause—maintain that it doesn’t. Seth Barrett Tillman, a leading proponent of this cramped understanding of the Clause, relies on a number of pieces of evidence in support of this claim (Gautham Rao and Jed Shugerman ably demolish much of that evidence here), but one of the major pieces of evidence on which Tillman relies is a list of “persons holding office under the United States and their salaries” put together by Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. According to Tillman, that list “did not include any elected officials in any branch.” Thus, he says, the document shows that “officers under the United States are appointed,” and thus the President—an elected official—is “not an officer under the United States” and is not covered by the Foreign Emoluments Clause. In the New York Times, for example, Tillman wrote that this document was one of “three good reasons to believe that [the Clause] does not” apply to the President.

As I discussed in my previous post, Tillman’s document is not the only one that’s relevant to understanding Alexander Hamilton’s views on who was, and was not, an “officer under the United States.” In fact, an “abbreviated version” of the list of officeholders and their respective compensation was printed in the American State Papers (a collection of legislative and executive materials from early in the nation’s history), and that “abbreviated version” does include the President.

Why the two documents, and what to make of them? In an amicus brief he recently filed in litigation brought by CREW and others in the Southern District of New York, Tillman acknowledged the existence of this American State Papers document, but he dismissed it as “an entirely different document (but bearing a similar name).” He denigrated its significance on the ground that it “was not signed by Hamilton” and is “undated.” It was, he says without any supporting evidence, explanation, or citation, “drafted by an unknown Senate functionary.” Ultimately, Tillman concedes that it is “probative of the legal meaning of Office . . . under the United States,” but not as probative as the other document that does not list the President.

Based on simply looking at the American State Papers document online, it was clear that Tillman’s characterization was, as I wrote in my original post, “not even remotely” accurate. The American State Papers document was clearly connected to the Tillman document (the first paragraphs were essentially the same); it was dated; and it purported to be from Alexander Hamilton (it was type-set and thus was not “signed” by anyone, but the concluding paragraph ends with, “All which is humbly submitted: ALEXANDER HAMILTON, Secretary of the Treasury”). Interestingly, although Josh Blackman, Tillman’s counsel on the amicus brief, took issue with other aspects of my original post, he did not respond to the part of my post criticizing their characterization of the American State Papers document. Indeed, even after Joshua Matz on this blog called Blackman out for failing to engage with that part of my post, he still did not defend these particular claims they had made in their amicus brief.

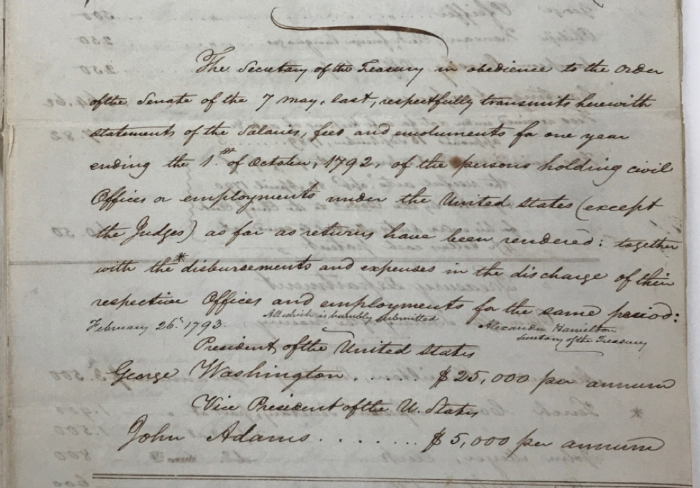

But my colleague Brian and I have now done a little more digging. We even took a trip to the National Archives to take a look at the original of Tillman’s document. And guess what we found in the very same box that houses the document Tillman emphasizes? The original of the American State Papers “abbreviated version.” And that original—the one that lists the President as an officer under the United States—appears to be signed by none other than Alexander Hamilton. And right beneath his signature are listed the President and Vice President and their salaries:

Our trip to the Archives also made it at least somewhat clearer why that abbreviated version exists. The original Tillman document was the cover letter that accompanied “some ninety manuscript-sized pages,” as Tillman explained in his amicus brief. Those 90 pages reflected documents that the Treasury Department had received from different departments across the federal government. Many contained a listing of every officer in their department—from the head of the department to the lowliest clerk. One of the documents provided the compensation of every lighthouse keeper in the country.

In the face of this volume of information, the Secretary of the Senate ordered that the report be “condensed,” and the original of the document that is included in the American State Papers is labeled “Condensed Report from Secretary of the Treasury with names, Compensation of all Officers in the civil employ of the Government.” The front page of the report contains a hand-written version of the original order of the Senate, crossed out, and then essentially the same paragraph that began the cover letter of the Tillman document: “The Secretary of the Treasury in obedience to the Order of the Senate of the 7 May, last, respectfully transmits herewith statements of the salaries, fees and emoluments for one year . . . .” (Rather than stating that he was transmitting “sundry statements” as in the original cover letter, Hamilton this time stated that he was transmitting “statements”—a logical change given that the condensed report was all one document.)

Now, perhaps there’s evidence out there that this document that appears to be from the Treasury Department and that bears Alexander Hamilton’s signature was not actually prepared by the Treasury Department. Perhaps there’s evidence that its inclusion of the President and Vice President doesn’t reflect the views of the man whose name it bears. But we haven’t yet seen it.

After listing the President and Vice President, the condensed report lists the compensation of all of the other officers from the various federal departments that were included in the original report, but this time in a single document. A comparison of the original and the condensed report reveals that they are not exactly identical, even putting aside the condensing—for example, the original report included a “List, Specifying the Persons of whom no information has yet been received on the subject.” In the original maintained at the Archives, one of the names on that list was crossed out, and compensation information for that individual was included in the condensed version. But on the whole the “condensed version” is exactly what one would expect—a condensed version of the many different documents that were submitted to the Senate in the original report. The one major difference is the inclusion of the President and the Vice President.

Finding this document doesn’t tell us why Hamilton didn’t include the President and Vice President in his original cover letter. We can speculate, of course. One possibility is that it was nothing more than an oversight. We know that in beginning to prepare this report in response to the Senate order, Hamilton asked the heads of various departments to send him information about the compensation of their employees. Perhaps no such letter was sent for the President and the Vice President, and so there was no document listing their compensation. When Hamilton put together the cover letter accompanying the original report, perhaps he viewed that letter as essentially a table of contents for the various documents he was enclosing—because there was no separate document listing the President and Vice President’s compensation, he didn’t include them. Assuming this other document is what it seems—a single, condensed report prepared by the Treasury Department to provide all of the compensation information—perhaps the Department used the opportunity of its preparation to remedy that omission, just as it added new salary information that it had subsequently received. Again, that’s just speculation. Jed Shugerman and Gautham Rao suggest another possible explanation here. This new document alone doesn’t make clear what happened.

But one thing it does make even clearer is that the American State Papers documentis not, as the Tillman amicus brief said, “an entirely different document” of “unknown provenance.” In his amicus brief, Tillman says that this “document of unknown provenance” should not be “favor[ed]” over the “Hamilton-signed original which was, in fact, an official communication from the Executive Branch responding to a Senate order.” And yet that is what the document he dismisses certainly appears to be. If there’s more to the story here, it should have been presented in the amicus brief, so the court and the public alike can assess the competing evidence.

As I noted in my first post, this Hamilton document isn’t the only basis for Tillman’s argument that the Foreign Emoluments Clause doesn’t apply to the President. But he’s long placed a lot of weight on it, including in the amicus brief he filed in the CREW case in the Southern District of New York. If Tillman wants the court and the general public to consider his Hamilton document, it’s important that everyone know it’s not the only Hamilton document out there. There’s another document, from the same box at the Archives, signed by Hamilton in response to an official Senate order, and that one explicitly identifies the President as an officer under the United States.