Reproductive Rights and Justice

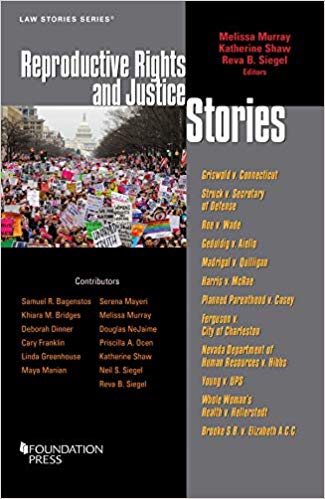

Take Care is pleased to host a symposium on Reproductive Rights and Justice Stories—an important new book edited by Professors Melissa Murray, Katherine Shaw, and Reva B. Siegel. Contributors will relate themes, stories, and case histories in the book to recent developments in American life and law.

This book examines the field of reproductive rights and justice, with attention to the dynamics of legal change inside and outside of courts—processes that one of us has long described as democratic constitutionalism.

What is reproductive rights and justice? The term “reproductive rights” is likely more familiar to readers. It commonly refers to a body of law that restricts government control of certain procreative decisions—key cases focus on sterilization, contraception, abortion, and, increasingly, assisted reproductive technologies.

Where reproductive rights are often defined as negative liberties that protect individuals against government coercion, reproductive justice thinks holistically about the conditions in which individuals make decisions about having and not having children. Reproductive justice considers the different forms of power, authority, and law that create obstacles to having children—and to raising children—in conditions of safety and sustenance. The field examines how relations of race, class, language, citizenship, sexuality, and gender shape decisions about reproduction and intimate life, through myriad bodies of law, as well as outside of “law” as traditionally understood—in the organization of communities, markets, health care, religion, and other structures of social life. Pursuit of reproductive justice cannot be attained in courts alone, but instead requires action across many bodies of law, and in many social domains, to redress inequalities in intimate life.

The stories collected in this book foreground law as a site of struggle over intimate life, but many do not foreground courts. Most chapters present legal change through a wide-angle lens that captures the multiple social contexts in which conflict over law occurs. This method for understanding constitutional change—democratic constitutionalism—focuses on popular engagement outside the courts, recognizing that debate over the Constitution’s meaning unfolds through and around courts and inside and outside of the state. On this account, courts matter. But so do other actors and institutions—from grassroots organizations, NGOs, and political parties to state and federal legislatures to administrative agencies and bureaucrats to interested individuals.

This book—and this symposium relating its themes to current developments in the law—could not be more timely. The news cycles are teeming with efforts to roll back protections for contraception and abortion, as well as heartbreaking images of migrant children and parents separated from each other at the border. As we see it, the cries to “end Roe” and “repeal the ACA” are of a piece with efforts to “build the wall” that would keep immigrants out. As the book explains, laws and policies that regulate intimate life and shape the way that families are formed, organized, and live are inextricably intertwined with policies that seek to define the nature of citizenship and belonging.

Perhaps most notably, the book’s publication coincides with a dramatic shift in the composition of the federal courts. Justice Anthony Kennedy, a long-standing voice in the Court’s disposition of reproductive rights and justice cases, has retired, and has been replaced by Justice Brett Kavanaugh. Changes in the judiciary’s composition are not limited to the high court. President Trump has already appointed one in five judges on the federal appellate bench. Past changes in the Supreme Court and lower federal courts have deeply shaped this body of law, as stories in this volume show—and we have every reason to expect current appointments to reshape many of the bodies of law whose development is explored in this volume

But the account of law and social change contained within these pages suggests that while the Supreme Court is an important player in these debates, it cannot settle the future of this body of law any more than it could a generation ago. Indeed, even as attacks on contraception take forms we have not seen in our lifetimes, there has been an explosion of activity outside of—and outside the reach of—federal law and the federal courts. New York has codified protections for abortion by statute, while the Kansas and Iowa Supreme Courts have found protections for abortion in their state constitutions; the Iowa Supreme Court has ruled that decisions about surrogacy are protected under state law, Kentucky has enacted a law mandating that employers reasonably accommodate pregnant workers, and a presidential candidate has outlined a plan for enacting and funding universal childcare—a proposal that has not been seriously considered since Presidents Nixon and Fordvetoed such legislation in the 1970s.

The book is organized to bring together cases that are canonical and non-canonical, and to put in conversation cases arising in constitutional law, family law, employment law, and criminal law. In the first chapter, Melissa Murray seeks to relocate Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) from its traditional perch in the constitutional law canon to the criminal law. As she explains, Griswold grew out of a criminal reform effort aimed at limiting the state’s use of the criminal law to police intimate life and sexual behavior. As such, Griswold—and its invocation of a right to privacy—is not merely an effort to liberalize access to birth control, but rather, is a challenge to the state’s authority to use criminal law to compel moral and sexual conformity.

We then move from Griswold, a traditional due process anchor for reproductive rights, to Struck v. Secretary of Defense (1971), a little known case through which Ruth Bader Ginsburg sought to ground reproductive rights in equal protection. As Neil S. Siegel shows, Ginsburg’s early and understudied brief in Struck highlights the relationship of pregnancy discrimination, sex discrimination, and abortion—and her understanding of women’s constitutionally protected rights to bear and not to bear children protected by equal protection and due process.

Reva Siegel and Linda Greenhouse’s chapter on The Unfinished Story of Roe shows how arguments for abortion’s decriminalization arose in politics—often as class-, race-, and sex-based claims on equal protection—and demonstrates how the struggle for and against abortion rights changed the stakes of the conflict, in the years before and after Roe. Their account of Roe’s genesis and evolution suggests that courts play a powerful yet limited role in defining the Constitution’s meaning. Deborah Dinner then depicts the welfare state considerations that shaped the Court’s decision to exclude pregnancy from the constitutional understanding of sex discrimination in Geduldig v. Aiello.

Maya Manian’s account of Madrigal v. Quilligan recovers the civil rights claims of ten Latina women who were sterilized under duress or without informed consent, and examines how intersecting dynamics of race, language, and poverty raise important themes in reproductive rights and justice. Likewise, Khiara Bridges’ telling of Harris v. McRae makes plain the intersecting forces of race, gender, and poverty that were at play in litigation challenging Medicaid restrictions on funding for abortion, and she examines the Burger Court decisions that rendered these forces of race, gender, and poverty invisible as a matter of equal protection law.

In her chapter on Planned Parenthood v. Casey, Serena Mayeri considers the oscillating political and legal dynamics that fueled threats to Roe and, ultimately, its reconstruction in Casey, in a fascinating history of constitutional change outside and inside the Court with deep resonance for our own historical moment.

In Pregnant While Black: The Story of Ferguson v. City of Charleston, Priscilla Ocen tracks one of the most notorious efforts to criminalize the reproductive choices of poor black women and the ways in which law failed to adequately address the various reproductive harms these women experienced as a result.

Samuel Bagenstos examines—and raises probing questions about—Chief Justice Rehnquist’s surprising opinion for the Court in Nevada Department of Human Resources v. Hibbs (2003), including the Hibbs Court’s apparent endorsement of feminist universalism—the notion that sex equality is best served by rules and policies that reject differentiation between women and men.

Kate Shaw’s chapter on Young v. UPS (2015) considers the strange bedfellows that have coalesced around the issue of pregnancy discrimination at different points in history, and considers whether such left/right coalitions might be coordinated around other issues of reproductive rights and justice.

Cary Franklin’s account of Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt (2016) focuses not only on the Court’s decision, but on actors such as Americans United for Life (AUL), an influential advocacy group partly responsible both for H.B. 2 and for the broader constitutional strategy that produced it.

Finally, Douglas NeJaime plumbs Brooke S.B. v. Elizabeth A.C.C., a groundbreaking 2016 New York Court of Appeals decision, for insights on how courts are addressing the legal questions of parental recognition as judges begin to give effect to principles of sexual orientation equality in the family.

The stories in this volume emerged as people, families, and communities joined to make transformative claims on the law. It has been exciting to learn about these episodes of legal change from the wonderful group of authors assembled for this volume. We invited this group to help reconstruct these stories for many audiences, but perhaps most of all for our students, who are entering careers in law at this dark and tumultuous time.

We are deeply grateful to the group of scholars who have engaged with the book for this symposium (and to Take Care for convening and hosting it), and we look forward to the contributions to come over the course of the symposium.

Tags:

Civil Rights Women’s Rights Reproductive Freedom Racial Equality