Why Jeff Sessions’s Reversal on Private Prisons Is Dangerous

In a memo cheered by prison reformers around the country last summer, Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates announced that the Federal Bureau of Prisons would stop using private prisons. That was then, this is now. Two weeks into his tenure, Attorney General Jeff Sessions withdrew Yates’s memo and reversed course. Stepping away from private prisons, he wrote, “impaired the Bureau’s ability to meet the future needs of the federal correctional system.”

The implications are clear. We are likely in for a federal incarceration boom and a dramatic expansion in contracting with private prison companies. This would be a boon for the companies, but potentially disastrous for the safety of corrections officers and prisoners.

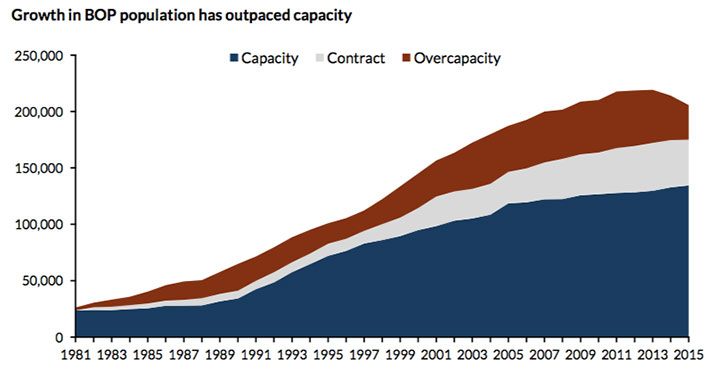

The federal government began using private prison companies to alleviate overcrowding. Due largely to the War on Drugs and severe sentencing measures enacted during the 1980s and 1990s, the number of federal prisoners rose from about 24,000 in 1980 to almost 220,000 in 2013.

BOP now operates 122 facilities that have a rated capacity — the number of people the prisons are designed to house, not including segregation and medical units — of 134,470. The federal prison population today sits at 189,041. Some of these individuals are in halfway houses or home confinement, but that still leaves about 41,000 people BOP isn’t built to accommodate. The Bureau contracts with private prisons to house 21,359 prisoners, mostly non-citizens who face deportation after completing their sentences. The remaining 19,499 are “overcapacity” — people BOP has to triple-bunk and house in classroom space in its own facilities.

Source: Charles Colson Task Force on Federal Corrections, Transforming Prisons, Restoring Lives, p.40 (Jan. 2016).

Unless BOP embarks on massive new construction, the federal prison population would need to shrink considerably to cease contracting with private companies. Toward the end of the Obama administration, that looked achievable. Thanks to sentencing reforms passed by Congress and the U.S. Sentencing Commission and changes to DOJ charging policy, the total population has declined for three straight years. Today, it sits at a 12-year low and the share in private prisons is down from 15% to 11%. DOJ anticipated that it would end its relationship with at least three of the twelve private prisons it currently uses by the end of 2017.

Weaning from private prisons, however, isn’t compatible with President Trump’s new enforcement regime. AG Sessions is enthusiastic about mandatory minimums and more drug prosecutions, which will swell the federal population overall. Moreover, Trump has signaled that more resources will be “devoted to the prosecution of criminal immigration offenses in the United States” — promising to grow precisely the group BOP incarcerates primarily in private prisons.

Private prison companies and their shareholders stand to profit handsomely. Three companies currently fulfill BOP’s contract needs for approximately $600 million annually: CoreCivic (known as the Corrections Corporation of America until rebranding this past October) and GEO Group, which are publicly traded, and the privately held Management and Training Corporation. CoreCivic and GEO Group saw their stock price crater the day of the Yates memo, dropping 35% and 40% overnight, respectively. GEO Group subsequently contributed $275,000 to a pro-Trump super PAC during the campaign, including a $100,000 check the day after Yates issued her memo, and hired two former Sessions aides as lobbyists.

Both companies’ stock spiked the day after the election, and then kept climbing. Each donated $250,000 for Trump’s inauguration festivities. The day after Sessions withdrew the Yates memo, February 24, both set new peak trading prices — CoreCivic’s stock up 147% and GEO Group’s up 105% since Election Day.

From a societal perspective, however, this is a grim turn of events. Recent evidence shows that private prisons are less safe than BOP facilities for both prisoners and officers.

The Justice Department’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG) has done vital work in this area. In an August 2016 report reviewing all private prisons housing federal inmates to BOP facilities of similar size, geography, and security level between fiscal years 2011 and 2014, OIG found higher rates of “safety and security incidents” at the private prisons. Inmate assaults on staff were more than twice as common, and inmate-on-inmate assaults were 28% higher. Officers also put the prison on lockdown more than nine times as often and used force 17% more often in private prisons. They monitored a significantly lower share of inmate phone calls for security threats than BOP because they lacked the proper technology and language interpreters. And there were more contraband cell phones, tobacco, and weapons found in the private prisons per capita. To be fair, OIG did find higher rates of positive drug tests and sexual misconduct incidents in BOP’s prisons. But overall, the report paints a clear picture: in the federal system, it is more dangerous to be either a corrections officer or an inmate in a private prison.

When OIG gave CoreCivic, GEO Group, and MTC an advance look at its report, the companies pushed back. Their inmate population was more dangerous, they said, because it consisted of “a homogeneous foreign national population” with a “‘one for all and all for one’ mentality” and many gang members.

OIG should assess these claims directly, but there is reason to be skeptical. For starters, BOP primarily sends private prisons people convicted of immigration and drug offenses and classified as low-security. In addition, other evidence suggests that the safety problems result from the way the private companies choose to operate their facilities. In May 2012, a prison riot at a CoreCivic prison, the Adams County Correctional Center in Natchez, Mississippi, resulted in the murder of a 24-year-old correctional officer and injuries to twenty people. The local sheriff initially claimed the riot began as a fight between rival gangs, but that proved untrue. According to the FBI, it started as a protest about poor medical care, inadequate food, and mistreatment. A separate BOP review found that systemic deficiencies in staffing and prison intelligence operations left prison officials unable to prevent the violence. The murdered officer’s family accused the company of creating “a dangerous atmosphere for the correctional officers.”

In December 2016, OIG finished an audit of the Adams facility and found that the underlying problems persisted. Much of the time, correctional officer staffing was lower even than at the time of the riot. Only 4 of 367 staff members spoke fluent Spanish, even though most of the 2,300 inmates were Mexican nationals. The prison often had only one doctor for the entire population. CoreCivic also employed people unqualified to get hired by BOP, paid them significantly less, and saw higher turnover than at comparable BOP facilities. Furthermore, BOP didn’t have a clear picture of the staffing shortage at Adams because of the way CoreCivic reported its personnel data.

That’s not all. Among OIG’s most disturbing findings was that private facilities were improperly housing new inmates in Special Housing Units—segregation cells where confinement can result in psychological and emotional harm. Not for any disciplinary or security-related reasons, but simply as a way station until beds opened up in general population, and for 20-25 days on average. Why was this happening? Because the private facilities counted SHU beds as general population space when they represented their capacity. So BOP would send prisoners there to alleviate their own overcrowding problem, unwittingly sentencing these individuals to segregation without a whit of due process.

It’s perhaps unsurprising that a profit-driven enterprise would pay officers less, skimp on staff, and put people in conditions that can cause mental deterioration just to resolve a space shortage. These actions increase the companies’ bottom line. But they endanger prison staff and prisoners alike. The fact that they will play a key role in managing the federal prison population under this DOJ should trouble us all.

Follow Chiraag on Twitter: @chiraagbains

Tags:

Immigration Regulation Civil Rights Justice & Safety Criminal Justice